CONFESSIONS OF A WILD-CRAFTER

Why I now always collect my own herbs

Christopher Nyerges

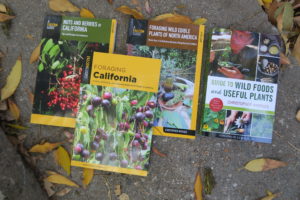

[Nyerges has been leading ethno-botany walks since 1974. He is the author of “Guide to Wild Foods,” “Foraging California,” “Wild Edible Plants of North America,” and other books. More information at www.SchoolofSelf-Reliance.com]

First, what’s a wild crafter? When I first heard the term, a wild crafter referred to a wholesale herb collector, someone who collected medicinal herbs from forests and woods and sold them to the middlemen in the herb business. These middlemen would then process these herbs and sell them to the packer, the company that would put the herbs into tea bags and boxes. Then the packaged herbs were sold to the health food stores nationwide, to be sold retail to people like you and I.

Though I had purchased wild herbs many times from health food stores, and even collected my own wild herbs many times, it never occurred to me what one had to do with the other. Then I happened to read an article in an outdoor magazine about a man who collected wild herbs and sold them to various middlemen, who then packaged the herbs and sold them to the neighborhood health food store.

The author of the magazine article provided the names and contact information for six or seven such middlemen who buy wild herbs. All I had to do if I wanted to be a wild crafter for money was to send them a list of the herbs that I could obtain in bulk. I sent a letter to every one of the buyers, listing the dozen or so herbs that I felt I could collect in sufficient volume to make it worth my while. I got two responses, and each told me how much they would pay me per pound of the dried herbs. Plus, they would pay the postage. The prices were less than what I expected, but I was just learning about the world of harvesting and farming, and wholesaling and retailing.

As an aside, the retailer – the owner of the brick and mortar store – expects to get their products for about 40 to 50% below the retail price. That percentage is how they pay their bills and stay alive. So in order for the middleman to make anything for their role, they have to pay the source of the product – in this case, me – even less. Just do the math, and you’ll see that if a box of some herb retails for $10, the store might pay $5, and the middleman has to make a percentage, and the collector –me – will make even less.

I didn’t know all this when I began. I didn’t know that the collector actually earns the least in the whole string of transactions before a box of herbs gets onto the store shelf. Nevertheless, despite all this, I told myself that I would still try wild crafting, hoping to make my money by volume.

I collected the herbs that the middleman needed, both native and non-native herbs. I laid out sheets of plywood up in my parents’ attic – which was always hot and dry – and I laid out the herbs to dry. I collected passionflower leaf and vine, yerba santa, black sage, bay leaves, epazote, curly dock, nettle, and a few others that were seasonally abundant.

I would typically spend several hours collecting, and then I’d haul the large bags and spread them out in my attic drying area. I always meticulously collected herbs, and always picked over the drying herbs to remove any foreign leaves or twigs. When dry, I’d pack the herbs into separate plastic bags, box it all, and mailed it off to the middlemen. I’d always weigh the dry herbs so I had some sense of what I would get paid. Also, because of my meticulousness, the herbs that I sent were always as close to 100% pure as possible.

I learned a lot about herbs and the herb business in this process. For example, some herbs reduced to powder when dried, and others remained bulky. I learned which herbs would earn me the most for my time.

After a few weeks or so of drying, I was always amazed to see how small of a box all those dried herbs fit into. It often seemed like a lot of work for so very little. Of course, I realized early that in the long chain of events, I was the one earning the least, and eventually, I quit collecting wholesale.

Then some months later, the middleman calls me and asked if I could get a supply of a certain toxic plant. Yes, I told him, I could, but I didn’t want to. Something seemed creepy about it. I asked him who would be buying those toxic herbs, and he just said he had a buyer, but I still said no.

He called me once more, asking if I could supply him with ginkgo biloba leaves. I told him that they grow all over town where I live, but that it would take me too long to get even a pound, let alone clean it.

“Look,” he explained, “just rake it up and put it all into a box and send it to me.”

“What?” I responded with surprise. “What about all the dirt and twigs and dog poop? It would take me too long to clean it.”

“Oh, just rake it up and put it into a box,” he responded. “As you know, we’ve always allowed up to 15% adulterant.”

I didn’t know that and I was shocked. I did not want to be a part of the chain supplying an impure product with up to 15% adulterant. I said no.

I was never able to get that “15% adulterant” out of my mind. Everything I ever sent to him had always been 100% pure – certainly, at least 99.999% pure. That was the only way I could sleep at night. The idea that anyone would accept 15% adulterant in the herbs that people would be using for tea and medicine was very troubling to me, and I never did that sort of wholesale wild crafting again.

I almost completely stopped buying herbs at the store because I realized that just about every herb I ever purchased was one which I knew where to collect in the wild. Plus, I also began to grow those herbs that didn’t grow wild around me.

In the years that followed, I would occasionally read about someone who purchased some herb tea from a health food store, packed by a “respectable company,” who experienced sickness, near-death, and at least one death that I learned about. When the tea in question was analyzed by authorities they discovered that the tea contained some other plant that shouldn’t have been there. You know – an “adulterant.” Sometimes the adulterant gets identified, sometimes not. And every time I read about such an incident, I think back to the middleman, telling me that 15% adulterant is OK.

While there have been efforts to standardize the wild crafting business, and make it safer for the consumer, most herbs today are collected from the wild. There are some that use herbs grown on farms, but they are the minority.

When you buy packaged herbs from the store, your safety depends on the personal ethics of the wildcrafter collecting the herbs that you will be consuming. And that’s the key – personal ethics when no one is watching and when it is super easy to “get away with” a compromised product. And when your time is money, and when more weight (even if it’s an adulterant) means more money, it is all too easy to compromise.

I’ve been a practicing herbalist for a very long time and encourage others to find natural ways to stay healthy, and get healthy. Learning how to grow the herbs you use, and how to identify wild herbs, is a great step towards getting outdoors more often, and towards your own safety.