MORE ON THANKSGIVING

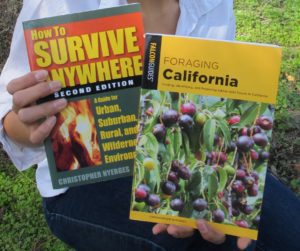

[Nyerges is the author of “How to Survive Anywhere,” “Foraging California,” “Enter the Forest” and other books. He leads courses in the native uses of plants. He can be reached at Box 41834, Eagle Rock, CA 90041, or www.SchoolofSelf-Reliance..com]

I met a man who began to discuss with me the column I wrote about the historical origins of Thanksgiving, and what happened, and what didn’t happen.

“I was a little puzzled after I read it,” Burt told me. “I wanted to know more. I understand that the first historical Thanksgiving may have not happened the way we are told as children,” he told me, “but how did we get to where we are today? What I understood from your column was that there are historical roots, and that we today remember those roots and try to be very thankful, but the connection was unclear.” Burt and I then had a very long conversation.

A newspaper column is typically not long enough to provide the “big picture” of the entire foundation of such a commemoration, as well as all the twists and turns that have occurred along the way. But here is the condensed version of what I told my new friend Burt.

First, try reading any of the many books that are available that describe the first so-called “first Thanksgiving” at the Plymouth colony that at least attempts to also show the Indigenous perspective. You will quickly see that this was not simply the European pilgrims and the native people sitting down to a great meal and giving thanks to their respective Gods, though that probably did occur. In fact, the indigenous peoples and the newcomers had thanksgiving days on a pretty regular basis.

As you take the time to explore the motives of the many key players of our so-called “first Thanksgiving,” in the context of that time, you will see that though the Europeans were now increasingly flowing into the eastern seaboard, their long-term presence had not been allowed – until this point. Massasoit was the political-military leader of the Wampanoag confederation, which was the stronger native group in the area. However, after disease had wiped out many of the native people, Massasoit was worried about the neighboring long-time enemies – the Narragansett — to the west. The gathering of the European leaders of the Plimouth Colony and Massasoit and entourage had been more-or-less brokered by Tisquantum (aka Squanto) who spoke English.

Yes, there had been much interaction between the new colonists and native people for some time, and this gathering of 3 days in 1621 was intended to seal the deal between the colonists aligning with Massasoit. The exact date is unknown, but it was sometime between September 21 and November 9.

Yes, historians say that a grand meal followed, including mostly meat. The colony remained and there was relative peace for the next 10 to 50 years, depending on which historians were correct in their reading of the meager notes. The historical record indicates that the new colonists learned how to hunt, forage, practice medicine, make canoes and moccasins, and much more, from the indigenous people. Even Tisquantum taught the colonists how to farm using fish scraps, ironically, a bit of farming detail he picked up during his few years in Europe.

Politicians and religious leaders continued to practice the giving of thanks, in their churches and in their communities, and that is a good thing. They would hearken back to what gradually became known as the “first Thanksgiving” in order to give thanks for all the bounty they found and created in this new world, always giving thanks to God! But clearly, the indigenous people would have a very different view of the consequences of this 1621 pact, which gradually and inevitably meant the loss of their lands and further decimation of their peoples from disease. Of course, there was not yet a “United States of America,” and it was with a bit of nostalgia and selective memory that we refer to this semi-obscure gathering of two peoples as some sort of foundational event in the development of the United States. And it is understandable from the perspective of a national mythology that the native people were forgotten and the “gifts from God” remembered.

My new friend Burt was nodding his head, beginning to see that there was much under the surface of this holiday. I recommended that he read such books as “1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus” by Mann, “Native American History: Idiot’s Guide” by Fleming, and others.

As I still believe, giving thanks is a good thing – good for the soul and good for the society. Just be sure to always give thanks where it is due!

Eventually, in the centuries that followed, Thanksgiving was celebrated on various days in various places. George Washington declared it an official Thanksgiving in 1789. However, the day did not become standardized as the final Thursday each Novembe until 1863 with a proclamation by Abraham Lincoln.

The gross commercialization of Thanksgiving is a somewhat recent manifestation of the way in which we have tried to extract money from just about anything. One way to break that cycle is to just choose to do something different.

When I used to visit my parents’ home for annual Thanksgiving gatherings, I disliked the loud arguing and banter, the loud TV in the background, and the way everyone (including me) ate so much that we had stomach aches! I felt that Thanksgiving should be about something more than all that. I changed that by simply no longer attending, and then visiting my parents the following day with a quiet meal. It took my parents a few years to get used to my changes, but eventually they did.

This year, before the actual Thanksgiving day, I enjoyed a home-made meal with neighbors and friends. Before we sat down to eat, everyone stated the things they are thankful-for before the meal. Nearly everyone cited “friends and family,” among other things. It was quiet, intimate, and the way that I have long felt this day should be observed. Yes, like most holidays we have a whole host of diverse symbols, and Thanksgiving is no different. And like most modern holidays, their real meanings are now nearly-hopelessly obscured by the massive commercialism. Nevertheless, despite the tide that is against us, we can always choose to do something different. Holidays are our holy days where we ought to take the time to reflect upon the deeper meanings. By so doing, we are not necessarily “saving” the holiday, but we are saving ourselves. As we work to discover the original history and meanings of each holiday, we wake up our minds and discover a neglected world hidden in plain sight.